This book is now out of print, but available online from used booksellers like betterworldbooks.com.

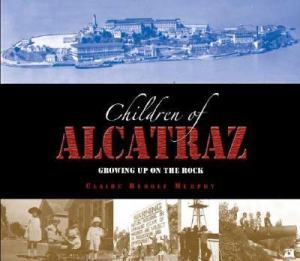

Alcatraz Island is one of the most infamous places in American history. The maximum-security prison on the “Rock,” once home to criminals like Al Capone, Machine Gun Kelly, and the Birdman of Alcatraz, has long since captured our country’s imagination. But what few people realize is that during the past 200 years, Alcatraz was not only home to criminals–it was home to many children, too! Over the years, the island has been home to the children of Native Americans, lighthouse keepers, military soldiers, and prison guards.

Alcatraz Island is one of the most infamous places in American history. The maximum-security prison on the “Rock,” once home to criminals like Al Capone, Machine Gun Kelly, and the Birdman of Alcatraz, has long since captured our country’s imagination. But what few people realize is that during the past 200 years, Alcatraz was not only home to criminals–it was home to many children, too! Over the years, the island has been home to the children of Native Americans, lighthouse keepers, military soldiers, and prison guards.

Imagine playing hide-and-seek in the prison morgue, having a convict as your babysitter, or having Al Capone as your neighbor. This compelling photo-essay profiles generations of children who had the unique opportunity of growing up on this isolated island in San Francisco’s shadow. With personal anecdotes, revealing interviews with the surviving Alcatraz Kids, historical documents, and archival and family photographs, Children of Alcatraz reveals a one-of-a-kind childhood sure to fascinate readers young and old.

Excerpt

Read an excerpt from the book.

Author Q&A

Read the author’s answers to student’s questions about Children of Alcatraz.

Reviews

While other books cover the history of Alcatraz Island for this audience, none of them give more than a brief mention of the many children who lived there over the years. Murphy’s clearly written history starts with the island’s use by Native Americans in the pre-Colonial era and continues through its various incarnations as a lighthouse, military post, and then prison. She follows the federal penitentiary years, the island’s rearming during World War II, the Native American occupation of 1969-71, and the island’s current incarnation as a National Historical Park. The young people who lived there were mostly children of employees and of the Native Americans during the occupation, but also included youthful prisoners. Liberally illustrated with black-and-white archival photographs, the book also includes print, AV, and Internet resources. While useful for reports, this title will appeal to general readers.

–Nancy Silverrod, San Francisco Public Library Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Most people associate Alcatraz with notorious criminals such as Al Capone, but few think of children. Some children, however, did grow up on “the rock,” and this is their story–from the earliest Indian children to those whose parents occupied Alcatraz during the 1969–71 Native American protests. In between, children of lighthouse keepers, soldiers, and prison authorities played on the grounds and called it home. A few photographs feature famous prisoners, but most are snapshots of the islands youngest residents. The anecdotal narrative, connecting photos and families, makes this more family album than wanted poster. The narrow focus may disappoint some, but it reveals a unique portrait of children who have generally been invisible. A list of further resources and a time line are appended, but no sources are cited.— Linda Perkins, Booklist. Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved

Editorial Review – The Pacific Northwest Inlander

LIFE IN THE BIG HOUSE

Years in prison, yet never accused of any crime.

Unlawful detainees? No, the subjects of Claire Rudolf Murphy’s book.

Published in The Inlander

Sept. 28, 2006

The Last Word: Rocky Childhood

by MICHAEL BOWEN

You should see the big eyes when I tell people that my wife did time in prison. Then I lean in confidentially for effect: Yep, five years at Soledad. Two years in San Quentin.

And it’s true, though Dannie Loriano has no criminal record. It’s all because her father worked his way up from prison guard to associate warden and then on to the California parole board. Yet Dannie says the best school she ever attended was a two-room schoolhouse inside the walls of a maximum-security prison. And what’s striking, in talking to my wife and to Claire Rudolf Murphy, author of Children of Alcatraz, is how normal the lives of prison guards’ families could be. Even when the neighbors were doing 25 to life.

The kids on the Rock, says Rudolf Murphy, played baseball on the parade ground. They played football with a white ball that could be seen in the fog. They hung out at the corner store. They held dances – there was even a lover’s lane. She’s describing what sounds like idyllic Bay Area lives back in the 1940s and ’50s. But then she recounts the “tradition, every Christmas Eve, that they would sing Christmas carols at the warden’s house – and then to the prisoners.” In memoirs, inmates admit that they wept to hear the children’s voices at Christmas.

During the years when Alcatraz was a federal prison (1934-63), it housed Machine Gun Kelly, the Birdman and, in a typical year, about 50 children – prison guards’ kids, mostly, but also the children of service per

sonnel and even the lighthouse keeper. Civilians tend to think that living inside a notorious federal penitentiary must somehow have been dangerous for the little tykes – yet in fact, says Rudolf Murphy, mothers worried more about their kids playing on ocean cliffs than about the prisoners. “Kids snuck around to places, as kids would, but in this case they were getting into places they were really not supposed to,” she says. “There were guard towers all over, and they thought they were getting away with stuff, but they were being watched.”

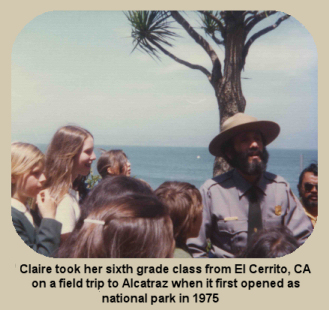

Children of Alcatraz had its origin some 30 years ago, when Rudolf Murphy took a bunch of sixth-graders on a field trip to the island. And what were the kids most curious about?

The escapes, of course: rifles and guard dogs, searchlights and city lights, barely a mile away over the freezing waters. Back in ’63, three inmates escaped and got themselves immortalized in a Clint Eastwood movie – but unlike all the other escapees (“either captured, or killed, or shot dead on the fence, or else their bodies were found,” says Rudolf Murphy), Frank Morris and the Anglin brothers were never discovered. Might they have made it?

You can see the school kids’ widening eyes. But then my wife knows all about prison danger. The better-behaved prisoners at Soledad, for example, were allowed to work as gardeners right outside the guards’ homes. “One gardener liked to build things for us – tepees, a mission church, a barn with fences,” recalls Dannie, who was 5 at the time. “But then my dad had him transferred away. He had murdered his wife.”

Dannie recalls that during her San Quentin years (two years inside the walls, then 15 years on an adjacent property), prisoners simply climbed over the fence every month or two. She remembers the red phone in her family’s home that, when it rang, made her dad holster his gun and hurry away. The light outside her bedroom window that turned red in case of a prison riot. Guards checking the trunks of cars and the backs of buses every time they left the gates. The playground rumor that, after every gas chamber execution, you’d be able to see a poisonous plume rising over Death Row.

Dannie recalls that during her San Quentin years (two years inside the walls, then 15 years on an adjacent property), prisoners simply climbed over the fence every month or two. She remembers the red phone in her family’s home that, when it rang, made her dad holster his gun and hurry away. The light outside her bedroom window that turned red in case of a prison riot. Guards checking the trunks of cars and the backs of buses every time they left the gates. The playground rumor that, after every gas chamber execution, you’d be able to see a poisonous plume rising over Death Row.

Living in a place where armed guards might interrupt his daughter’s slumber parties, naturally a prison official like Bob Loriano would have worries and even nightmares. The toll on prison families could be heavy. Dannie recalls guards’ kids getting heavily involved in drugs and prostitution while still in high school; she remembers one guy who actually returned to San Quentin as one of the inmates.

The Alcatraz kids had their share of troubles too. Even if they have stories of the occasional alcoholic or abuser – “the kinds of problems you would find in any neighborhood,” says Rudolf Murphy — for most of them, the Rock was simply home. That’s why the most historically significant event in the history of Alcatraz, the Indian occupation of 1969-71, has upset so many conversations at Alcatraz alumni reunions.

When 68 unarmed Native Americans commandeered Alcatraz in protest of two centuries’ worth of broken treaties, the media played up the story, says Rudolf Murphy. “It was the whole underdog thing,” she says. “Everyone in the country knew that the Indians had been so poorly treated in all those wars. The San Francisco Chronicle ran the story the night they landed. Two days later, it was Thanksgiving, and restaurants in the city brought over boatloads of food. The Black Panthers came over, the motorcycle gangs showed up – everyone came out and partied on the Rock.”

The Alcatraz kids, now elderly, have different recollections. Even if the occupation marked the beginning of the American Indian civil rights movement, what they remember is the trash and the squalor: their former homes and neighborhood, desecrated. Because while most people associate places like San Quentin with guys in striped pajamas, and while tribal leaders can point to Alcatraz as the birthplace of Indian activism, for the kids who grew up on the Rock, it was simply a place they called home.